Javier Manterola Armisén at the opening of the Constitution of 1812 Bridge in Cádiz, Spain

Eighty this year and brimming with gentle humour, Javier Manterola Armisén claims to have no intention of retiring and says that while he still has something to give, he will do so. But change is in the air at Madrid-based engineering consultancy Carlos Fernández Casado, and now that the impressive, 3km-long Constitution of 1812 Bridge in Cádiz is finally complete, Manterola is willing to hand over the pencil to the next generation. “If there is one thing that I wish this office to carry on doing, it is designing. To design one has to draw, and young engineers have the right to try, as I did when I started here.”

Manterola co-founded engineering consultancy Carlos Fernández Casado in 1964 with Leonardo Troyano and Troyano’s father Carlos Fernández Casado, who had taught the young engineers at the Technical University of Madrid.

“As soon as we started the company we immediately began taking on the projects before they reached Casado. We had a great willingness to do things and although he found himself almost displaced by us, he allowed us to take on these projects. I am grateful for that; it is the reason why I am pushing these young engineers to draw. I am very clear in my mind that they have to start to make themselves engineers. They have to dare to create.”

Daring to create is a defining characteristic of Manterola’s work, and one that manifested itself even before he had completed his degree in civil engineering. At the tender age of 25 he was contacted by construction company Huarte who offered an opportunity to work with architect Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza, a fellow native of Navarre, on an unusual high-rise building.

Torres Blancas, Madrid, Spain. Image: José María Sánchez de Muniáin

Completed in 1968, Torres Blancas is an 81m-high residential and office building in Madrid whose structure consists of cylindrical units crowned by overhanging rounded balconies. The building is unusual because it is not supported by beams but, instead, the support is provided by the reinforced concrete external walls and internal structure. Architect Oiza’s vision was to create an organic building where the stairs and lifts served as the trunk of a tree and the cylindrical overhanging balconies as the leaves.

Working on Torres Blancas gave Manterola his first taste of the practical, often problematic, interaction between the design, engineering and construction functions of a complex project. “Oiza and I spent eight months talking about Torres Blancas before we even started the project. The questions were: what is the structure of the cylindrical units?

“What is the intersection between the vertical wall and the overhanging balcony? Oiza would say it would be such and such, and that the balcony would then be embedded into the wall. I would say no, because the intersection had to be able to flex, because the rigidity of the cylindrical unit was greater and it could destroy the wall. It was a very long discussion. A long time later, when we were approaching the upper level, a very skilled foreman looked at the plans and said, ‘Look at those, they are rubbish! It’s going to be built another way and you can add more reinforcement if you want but I’m building it this way because it can’t be built any other way and the formwork will cost too much.’” Although there have been plenty of similar instances across the 200-plus projects that Manterola has worked on during his career, this one was a defining moment for him: “I remember thinking, ‘What was the point of all my theoretical musings, of putting everything in its place, of using the exact material, if they are not going anywhere because, at the end of the day, comes the reality of the construction process?’”

After two years with construction company Huarte, Manterola joined the Eduardo Torroja Institute of Construction Materials in Madrid, researching punching shear of slabs, bending and shear failure of girders as well as mechanisms of movement redistribution in the deck of prefabricated girder bridges.

At the time, it was widely accepted that, in order to design a bridge, a young engineer had to work in a construction company to experience and see for himself the problems of a building site. “But I never understood that. The issues engineers face on site are related to contracts, salaries, whether it’s the right type of concrete, whether the formwork is correct - all important functions, but they are not technical issues.” Working at the Torroja Institute, however, offered a golden opportunity to get inside problems and, as he describes it: “Live the deformations, imagine how things are going to turn out and ascertain whether what you have imagined is correct or not. Pure investigation.”

A year and a half into the research position at the Torroja Institute came the opportunity to co-found CFC, in 1964. With three mouths to feed on a meagre researcher’s salary, Manterola agreed: “I did think about it because my time as a researcher was very personal, and I liked penetrating the problems. I liked not taking the accepted solution but instead getting right into the issues. But I missed drawing.”

Drawing bridges had become a compelling habit for Manterola, and one to which he owes an intimate knowledge of bridge design. He would draw constantly on blue hard-backed notebooks, a way for him to internalise and understand the structures of bridges: “I spent my life drawing, watching TV and sketching the bridges of the world. I have mountains of notebooks.”

Sancho el Mayor Bridge, Navarre, Spain. Image: www.infotografia.es

In 1978 he collaborated in the construction of the Sancho el Mayor Bridge, a 146m-long cable-stayed bridge over the Ebro River in Navarre, northern Spain. Shortly afterwards, only a year later in fact, came a project that was to bring CFC and Javier Manterola to the world’s stage. It was the opportunity to design a record-breaking 440m-long cable-stayed bridge over the Barrios de Luna reservoir in the province of Leon, north Spain.

This bridge, later named the Ingeniero Carlos Fernández Casado Bridge in honour of the work carried out by CFC’s founding member throughout Spain, snatched the world record for cable-stayed bridges from the 404m-long Saint Nazaire bridge over the river Loire in Brittany, France, and held onto it – for concrete cable-stayed bridges – until 1995.

“We went from 146m to 440m, a colossal step for us because no medium-sized cable-stayed bridges had come up in between Sancho el Mayor and Barrios de Luna,” recalls Manterola: “But I have always felt that going beyond what one has done [in the past] is very important. Because you never know enough you have to have confidence in yourself and the tools at hand.”

Barrios de Luna Bridge, León, Spain. Image: www.infotografia.es

Barrios de Luna caused Manterola many sleepless nights, he admits, and he and Troyano even went so far as visiting Fritz Leonhardt in Stuttgart to solicit some advice: “We said to him, ‘We are going to build the Barrios de Luna Bridge. We have done very few cable-stayed bridges, but we are clever and very hard working. If you give us two ideas, that’s it, we will be happy.’ And Leonhardt said, ‘I do not sell ideas, I sell projects’!”

In fact, so highly regarded was German engineering in the 1970s that during the Barrios de Luna bridge project many people would ask where the German engineers were: “We would answer, ‘No, there aren’t any. It’s just us.’ And they couldn’t believe it! We knew a lot about what had been done around the world but then you have to attempt it for yourself. That bridge brought infinite problems to us, but we lived to build.”

This spirit of boldness is something that Manterola says is visibly apparent throughout the industrial revolution in England, an historic period he knows well. He points at the 176m-long span of Thomas Telford’s Menai suspension bridge which connects the island of Anglesey to the mainland of Wales. “Telford claimed that it was impossible to construct a suspension bridge with a longer span, but Brunel went to 214m with the Clifton Bridge. Did Brunel know more than Telford? No he didn’t, but he had intuition and he dared to contradict what the great father of engineering had said.”

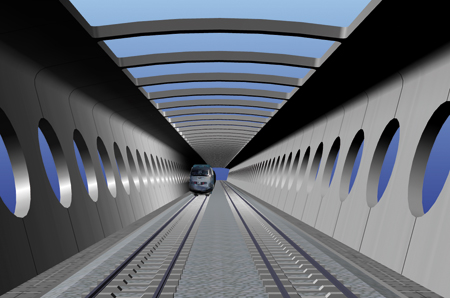

Another project he remembers fondly is the Osera Bridge that crosses the Ebro River in Zaragoza, north-east Spain, part of the high-speed rail link between Madrid and Barcelona which was completed in 2001. This five-span, 546m-long tubular Vierendeel-truss bridge features unusual circular openings on the side ribs that infuse it with a distinctly retro feel reminiscent of the futuristic rail carriage designs of the 1960s: “The project was directed by an engineer with an open mind who trusted me and let me get on with it. I proposed the tube, and when construction began, other engineers more important than him would say that it couldn’t be like this. They were worried that the design would delay the construction process and disrupt the railway service. Then other engineers came and said that it was an ecological area with special birds, and that it was obvious that the bridge would start whistling like a flute when the train would pass through the tube, scaring the birds. I can’t remember how I convinced them that it wouldn’t whistle, but in any case in the end it didn’t. It was difficult but there were no problems in the actual construction process.”

Osera Bridge, Zaragoza, Spain. Image: www.infotografia.es

With a breadth of experience in projects as diverse as his many bridges and buildings such as the Bilbao Bank, Atocha railway station, Torres Colón and the Indurain velodrome, Manterola is very certain which he prefers. Bridge projects win, hands down; an engineer, after all, gets to own a bridge project. “I have found working with architects very annoying because they always have the last word,” Manterola admits. “I learned a lot from Oiza, for example, and he was a great man. I also annoyed him, and he would say, ‘When I work with architects and they criticise something, I say an engineer did it. And when I speak with engineers, I say it was done by an architect!’

“But I didn’t want to work with people who at the end of the day would always have to be right. With bridges… that way I walk free and that’s it.”

It’s not just the freedom that bridge design afforded him that nourished Manterola’s talents and enabled him to excel in his chosen profession, but also a natural love of the arts.

Born in Pamplona, Navarre, northern Spain in 1936, Manterola finished his high school studies near the top of his class. At the time, he remembers, career choices for bright students were quite defined. Those good at drawing were architects, those more inclined towards languages and the arts joined the diplomatic service, and those who understood mathematics would be directed towards civil engineering.

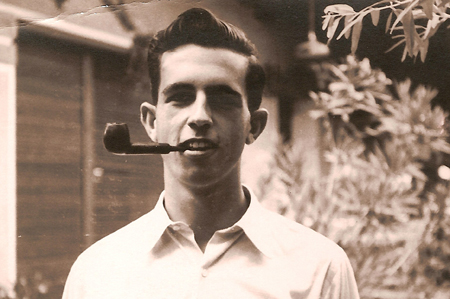

Javier Manterola Armisén, 21 years old

A love of the arts and classical music have played a significant part in Manterola’s life from his early years right through to when, as an undergraduate in Madrid, he would frequent the Prado museum on a daily basis. Among his favourites writers as a young man were Aldous Huxley and Camus, which he puts down to a preference for a genre that sits in that middle ground between the novel and philosophy. He found philosophy a useful discipline for learning how to ask the right questions, rather than for finding any answers.

This deep-seated love of the arts in conjunction with his work in engineering and modern architecture led to his election in 2006 as a permanent member of the 56-strong Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid. This venerable institution, which was founded in 1752, aims to promote artistic creativity as well as protect Spain’s cultural heritage. Its past members have included Francisco Goya, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Antonio López García, Juan Luna and Oscar de la Renta.

Engineering sits naturally in the San Fernando Academy and many engineers, Manterola points out, are attracted to music and philosophy perhaps because of their connection with mathematics. Never afraid to investigate this relationship, he recounts how he once tried an experiment to ascertain whether music could inspire engineering. “One day I thought, I’m going to see whether I can design this bridge whilst listening to Bach. And I started and… nothing! Nothing special came to mind!”

Práxedes Mateo Sagasta Bridge, Logroño, Spain.Image: www.infotografia.es

A subject that is clearly close to his heart, Manterola talks at ease about art and the beauty of engineering. Currently he is determined to help fellow members of the academy – painters, graphic designers, sculptors, musicians – to appreciate engineering’s artistic qualities: “They do understand, but they tend to confuse the qualities with size, for example the bridge in Cádiz which yes, has an impressive size, but that is not the main issue. Size matters but it doesn’t define good engineering.” He brings up the 140m-long Práxedes Mateo Sagasta Bridge over the river Ebro in Logroño, capital of the Rioja region in Spain. It features an arch over the central deck for vehicles, while two separate pedestrian decks suspended from the arch by cable stays curve separately around the central deck. “That bridge has many interesting aspects going for it and, through presentations, I’m attempting to explain to fellow members of the academy how it works,” he reveals. “If you don’t understand art or architecture and you go to see Velázquez’s Las Meninas in the Prado or visit the National Gallery in London, you won’t understand anything – it’s the same with music. One has to understand the resisting forces in the bridge, yes, but all those behaviours come together in the end and become a form which has meaning.”

It is no easy task. Unfortunately, he believes, most of what is written by engineers on the subject of aesthetics is not very good. “Often they say very nice things but they don’t ever go into the essence of what makes a piece of engineering aesthetically beautiful.” He remembers being in Paris at a conference where Michel Virlogeux presented the Millau Viaduct: “It is a good bridge, but there weren’t any powerful [aesthetic] arguments behind it. It couldn’t be expressed at a level similar to Freyssinet’s work, for example.”

Manterola is writing a book on the subject of engineering as a work of art which he hopes will also help influence how the history of bridge engineering is regarded and taught. Warming to the subject, he admits that the concept of art is a confusing one, with the clearest definition being that art is whatever aesthetes say is art. “I’ve seen Damien Hirst’s work in London, and he is an artist because the aesthetes say he is. I am hoping fellow members of the academy discover the beauty in bridges.”

It is commonly claimed, he says, that throughout the 19th century engineers were not concerned with aesthetics and consequently the results were flawed. “I’ve seen the opposite. It is due to the fact that they were not informed by aesthetics that they broke new ground, which led the world of art to change its views on architecture.”

Notwithstanding his strong views on aesthetics, he has lectured very little on this subject to his students whilst chair at the Technical University of Madrid for 30 years from 1976 to 2006. He’d thought about it often, but he concluded that aesthetics was something personal that one had to find within, not learn. “One doesn’t sit down and say, how do I do an aesthetic bridge. I have never heard a painter or musician say that they are going to create a work of art. A work of art isn’t created, it is expressed and if the result is fundamental or formidable then it begins to be called art. It is a personal expression of its world, and it is the same with bridges.”

Whilst Manterola no longer travels much, due to a fall three years ago that broke two vertebrae and left him with a permanent tingling in his hands, he has journeyed widely. In the UK he admired bridges such as the Forth Bridge and he followed in the footsteps of pioneering engineers who invented new methods of construction as a result of advances in construction materials: “Stone as a construction material for bridges has its own genesis as to why it was used and how it works as a material, and I’m reading something about it at the moment. Stone has its personality and one can work with it in a determined way. But it has nothing in common with working with steel, which is why the results have to be different.”

The role of building materials in bridge construction is a subject that fascinates him. Everything new in engineering, he says, comes from the construction materials. The use of composite materials has some way to go because the issue of connections still has to be resolved. The materials are expensive, are light, but susceptible to the effects of wind.

With this deep-rooted interest in the use of materials and form, perhaps it shouldn’t then come as a surprise that among the bridge engineers whose work he admires is Jörg Schlaich, who was responsible for the ground-breaking design of the canopy roof of the 1972 Olympic grounds in Munich. “He’s the one who comes closest [to my idea of aesthetics], but perhaps his education on aesthetics wasn’t as strong as mine.”

He’s not, however, a fan of some of the neo-futuristic work that has been in vogue in some parts of the world, which he describes as leaving him ‘unsatisfied’. He particularly dislikes the 1992 Alamillo cantilever spar cable-stayed bridge in Seville, which spans the Canal of Alfonso XIII. He describes it as more of a sculpture than a bridge – and an old-fashioned, costly sculpture at that. Manterola knows his mind when it comes to bridges.

Today, CFC is a busy office with projects in the UK, Ireland, USA, Colombia, Ecuador and the Middle East, the consequence of the Spanish market drying up several years ago during the financial crisis. Much of CFC’s international work comes via Spanish contractors who open the door for CFC, particularly when complex projects require specialist expertise that isn’t always available locally. Such consulting projects are not as satisfying as design projects, says Manterola, and the results can be questionable: “It is often the case in Anglo-Saxon countries that the design of a bridge is passed from the engineers to the architects, who give it the aesthetic touch. This is a bad formula and it has always worked badly. Like all structures, bridges have their own personality which, if you are not in them, you cannot see. Sometimes we make suggestions and we are told a design has already been approved so there is nothing more to do. In these cases all we can do is ensure that the bridge is not going to fall down.” Also challenging is the level of management in large modern construction projects: “In Spain we are not accustomed to so much control and so many questions. And if you don’t agree with something, it leads to further discussions and time.”

Alcántara Reservoir Bridge, Cáceres, Spain.Image: www.infotografia.es

Asked if there are any bridges left that he’d like to build, and despite having already said that size doesn’t matter, a glint comes to his eye: “I’ve built many bridges, but yes, I would like to build bigger bridges!” Perhaps with a touch of envy, he brings up the Third Bosphorous Bridge, which has a 1,408m-long span: so why this obsession with size? “Because for the engineer, span and size are fundamental. The whole history of engineering is founded on going further. But don’t think that I’m not satisfied with what I’ve done, it’s just that it’s always possible to do more.”

That large projects hold little fear for him is also in evidence with work that never made it to the light of day. When King Hassan II of Morocco and the Spanish government looked into building the so-called Pillars of Heracles Bridge from Morocco to Gibraltar, it was to CFC that they turned. The most direct route for the Gibraltar crossing, remembers Manterola, required 900m-deep piers. The alternative, which followed an ‘s’ shape, required 300m-deep piers and spans of 3km. “Whichever way we looked at it, it was extremely expensive. We concluded that it would be cheaper to buy a boat for every Moroccan that wanted to cross the Strait of Gibraltar than to actually build the bridge.”

At present Manterola is gathering together all his projects with the intention of publishing a book. Bearing in mind that he’s already won many high-profile bridge awards, he is not looking for recognition: “I’ve travelled widely to see other people’s bridges, such as Freyssinet and Schlaich, and I’ve learned from them. That is what I want, that other people look at my work and think, ‘Look how Manterola solved that problem.’ That is the greatest accolade for engineers, not [winning] 50 prizes, but rather that young people find an answer in their work.”

As I prepare to leave Manterola’s office, I cannot resist one final question. What is it like seeing his creations everywhere in Spain? “That is what I enjoy the most, seeing my own work. It’s fantastic. I remember when I did Barrios de Luna, 29 years old. At first I looked at it and I didn’t think it was possible. Then, when you do it, you get a feeling of… creation, of achievement. You get a real sense of joy. I’m not unhappy with my work. I don’t know why a bridge is a good bridge, I can’t explain it, but I know when a bridge is good or bad. It’s like wine. How do you explain it?” I can’t answer that, but if anyone can articulate what makes a bridge beautiful, it’s probably Javier Manterola Armisén.

Constitution of 1812 Bridge in Cádiz, Spain